STUART M R HILL.CO.UK

HOME | BIOGRAPHIC | PERSONAL IDENTITY | RESOURCES | FACULTIES | INTERESTS | PLACE TO THINK | POLITIC | CONTACT

PROJECTS

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Origins and Craft of the Wooden Roofing Shingle (Shake)Step by step guide.

Wooden Shakes; A Centuries Old SolutionHand Crafted Shakes

Traditional handmade shakes (colloquially known as ‘Shingles’), made from locally sourced chestnut and oak.

Ever admire an old house covered with weathered shakes...those long shingles ole’ timers used to

Shakes are one of nature’s most attractive roofing and cladding materials. Natural beauty, durability and eco friendliness are some of the many advantages of choosing this unique material for your property.

Shingles & Shakes can be made out of oak, chestnut, larch, western red cedar and eastern white cedar. In time the colour of the wood will turn to an attractive natural look and feel through the influences of the weather, and will blend in with the surrounding environment.

Through the natural preservatives in the wood this type of covering is extremely durable and very low maintenance.

Shingles and shakes are typically cut from salvage logs and dead trees left over from logging. What is potentially a waste product is transformed into a long lasting roof cover with a minimal carbon footprint.

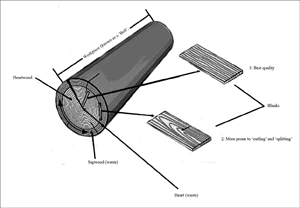

Every shingle is unique, each one being made by cutting a ‘bolt’ from a trunk and splitting or sawing blocks of wood or "shake blocks" from the ‘bolt’. Splitting the ‘block’ by hand with a froe and mallet gives a rougher surface to the shake than the more uniform shakes created by sawing when it is called a ‘shingle’, and whether we choose to split or saw depends on your individual requirements. Shakes look great on the roofs and even walls of almost all building’s, Shakes can be used on the following:

Roofing materials have seen radical changes over the years; yet one common material has remained the same almost from the start of New England’s history. Early 17th century settlers made their homes in basic structures that drew heavily on traditional English heritage, the use of wood shingles flourished in the American colonies and particularly ‘New England’ thanks to the abundance of trees, as similarly with many Scandinavian counties. The practice of using shingles for the roof as well as the walls of homes and farm buildings continues to this day. It is possible to make shingles today as they were made in colonial America.

By 1650 it was obvious that roofs of wooden shingles were the answer. In England such a practice would have been horribly wasteful of wood but here, timber was available in abundance.

The colonial roof started with a log bolt nearly three feet long. Wood slices about a ½” thick were split off with a froe and mallet. The bark was trimmed and one end was tapered with a draw knife on a “shaving horse”. The extreme length of early shingles came about for at least two reasons: first the horizontal wood strips or purling applied to the roof rafters for thatching were widely spaced and this traditional measurement was retained, secondly the length allowed three overlapping courses requiring half the nails – two shingles for the nails of one, a significant factor at a time when hand-wrought nails were more costly than the shingles themselves.

By the middle 19th century, machinery and transportation saw wood shingles become available nationally and standardized through mass production. Their availability and price along with inexpensive nails led to new ideas of how to use them. In the Shingle Style Architecture of the 1890s, shingles became the decorative frosting on the cake as well as simple, effective protection against the weather. As design elements shingles appeared on small cottages and grand houses alike, all of which are well-represented across America and much of Scandinavia.

A properly applied wooden Shake roof should last thirty-five to fifty years, but do require a measure of maintenance. Wood roofing shingles were commonplace in early America and across Scandinavia, not only because of the abundance of timber, but also because of the relative ease with which they could be fabricated and installed. Made from a variety of locally available trees, early shingles were hand split with a mallet and froe and then dressed or smoothed with a draw knife to ensure they would lay flat on the roof, and prepared this way they are correctly called ‘Shakes’.

The introduction of water and, then, steam powered saws in the early 19th century revolutionized the shake/shingle industry by making possible the mass production of uniformly cut and smoothly finished shingles that required no hand dressing. Despite such technological advances, hand split shakes never entirely disappeared. In fact, during most of the 19th century a thriving split shake industry existed and thrived across all regions of the world where they had historically been used and beyond. Reportedly a good ‘Shingler’ could tell merely by smell whether a log had been blown down or broken off, the former being the more desirable since it was less likely to be decayed. An expert worker could mine and shave up to 1,000 shingles a week. Today, although wood shingles represent a relatively small percentage of the roofing market, they remain a fashionable material for custom houses as well as restoration projects.

The life of a wooden shake roof can vary widely depending on the wood species of shakes being used and the treatment of the wooden roof shakes with preservative.

Wood shingles are sawn in 16", 18" and 24" lengths and are installed overlapped to produce two layers of shake material covering the roof which are in turn attached by nail to a felted and battened sub-structure. Wooden shakes (a split rather than sawn product) are thicker than sawn wood shingles (but can still have splitting or installation defects). Wood preservatives can make a significant difference in the life expectancy (and in some cases fire resistance) of wooden shingle or wooden shake roofs, depending on the wood species of the shingles or shakes and the preservative used. Traditionally wooden shingles and shakes were treated with copper or copper arsenate compounds to resist insects and rot; some shingle and shake treatments include chemicals that help the roof resist oxidation from sun exposure as well. Shakes are classically made by bucking a suitable log into segments, and then splitting these segments into flat pieces of wood called blanks, which are the shaved and trimmed into evenly sized shingles/shakes. While this process may not sound difficult, it is in fact quite challenging to actually produce uniform, smooth and even shakes. In modern times, this process is side-stepped altogether in favour of a power saw, a time saving cheat which actually produces “shingles” and not “shakes”. Shakes are wooden shingles which are split, rather than cut and create a distinctive feel, texture and appearance and have been used for roofing and cladding for centuries and is an age old English traditional craft.

As fresh wooden shakes age, they weather into a greyish or tawny gold colour and many may darken into richer colours. A variety of timbers are used to make shakes and this largely depends on the region in which they are made due to availability. But as a general rule, they are made from woods that are naturally resistant to infestation with insects or other locally common disease and rots and a suitable grain run. Wooden shakes can be found in many parts of Northern Europe and in other regions of the world where trees are relatively abundant. Shakes, for example, often appear on traditional homes in the United State and rural cottages in Scandinavia.

Chestnut.

The wood of the chestnut tree is hard wearing whilst also retaining good flexibility. It is easy to work with and only shows minimal contraction. It is resistant to water/rain making it an ideal roofing/cladding material. Chestnut is of the same family as oak, and likewise its wood contains many types of tannin. This renders the wood very durable, gives it excellent natural outdoor resistance and saves the need for other protection treatment. The chestnut shake will deliver long term performance. Chestnut timber is a gracious decorative timber. When in a growing stage, with very little sap wood, a chestnut tree contains more timber of a durable quality than an oak of the same dimensions.

Chestnut is often chosen for historic and heritage projects but are equally at home as part of a modern architectural project when their characteristics can deliver unparalleled rustic charm to a structure.

Many thanks for your interest.

Prepared by Stuart M R Hill

|

©

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed on this website, by either myself or any other contributors, are mine and or their own, and are not necessarily those of the publishers, authorities or such like as a whole or in part. Readers are urged to verify independently, any statements on which they may wish to rely as it cannot be guaranteed that any such statements are correct.No liability will be accepted by Stuart M R Hill, Contributors, Members, Webmaster or Web host for any situation arising out of use of information on this site.Anyone using such information does so entirely at their own risk.Please note that Stuart M R Hill or Contributors takes no responsibility for the contents of external websites that link to or from this site.

|

HOME

Webmaster: Stuart M R Hill - Developed with Adobe Dreamweaver