LIFE IN A MIXED STATE

a village idot's struggle to find a path to freedom

A Work in Progress

Prologue

The early Years: 67 to 79

Born in the tranquil town of Rayleigh but raised amidst the vibrant life of Leigh-on-Sea, my formative years were defined by strict discipline and unyielding expectations. Leigh-on-Sea, once a quaint fishing village, had evolved into a bustling community—a fitting backdrop for a childhood rich in challenges and lessons. My mother, a woman of immense strength, enforced structure with a firm hand, shaping the foundation of my character. Meanwhile, my father, an ingenious mind and a former Ford research engineer, later ventured into entrepreneurial success. From pioneering a groundbreaking 350cc three-cylinder motorcycle known as the KRM to owning a petrol station, workshops, and an M.O.T station, his achievements left an indelible mark on me. Despite their union dissolving when I turned 18, my mother's resilience remained the driving force in our family.

My childhood wasn’t without challenges. Social workers intervened when I was just seven, and strained relationships with my younger sister would later alter the trajectory of my life. Still, the echoes of my heritage spoke of ambition and skill—my maternal grandfather, a renowned plumber until a debilitating stroke, and my paternal grandfather, an esteemed engineer at Sage of London. Their legacies intertwined with my burgeoning identity.

Cold Reality Hits Home 79 to 86

Adulthood began tumultuously. At 18, a misguided decision led to a six-year prison sentence for armed robbery. The stark walls of incarceration became my crucible, forcing reflection and determination. While in prison, I seized the opportunity to equip myself with skills for the future, earning a City & Guilds qualification in welding. Upon release, I sought to rebuild my life, first trying to emulate my father’s path in the motor trade but soon realizing my aptitude lay elsewhere.

This era was marked by emotional upheavals and severed ties, including a rift with my sister that never healed. Yet, it was also a time when resilience and resourcefulness began to define me. Life was harsh, but the lessons were invaluable.

My Golden Years: 87 to 98

The late 1980s brought a wave of success and self-discovery. I found stability in sales, earning an impressive £1,200 weekly under the mentorship of Leonard Todd, who became a lifelong friend and guide. During this period, I ventured into property development, laying the groundwork for a career that would sustain me for decades.

Amid professional triumphs, my personal life flourished briefly. I married and welcomed my daughter, Abigail, into the world. Her name, meaning "father’s joy," symbolized hope and renewal. Yet, cracks emerged. An affair ended my decade-long marriage, marking the beginning of a journey filled with lessons on love and responsibility.

Travel became a significant outlet during this phase. Seven months in Spain and later a year in New Zealand exposed me to diverse cultures, shaping my worldview and enriching my life’s tapestry. It was also during this time that my father remarried, and I was introduced to Phil Culmer, one of his second wife’s sons. Although I initially disapproved of the relationship, Phil and I quickly formed a bond. Four years my junior, Phil became a steadfast friend, mentor, and collaborator. His intellect and strategic thinking complemented my drive, making him an integral part of many of my ventures. From legal battles to entrepreneurial pursuits, Phil’s unwavering support left a lasting impact.

The Long Winter of Discontent: 98 to 2001

Despite the momentum of my golden years, the turn of the millennium ushered in a period of struggle. A violent encounter at a cashpoint escalated into a serious altercation, resulting in another two-year prison sentence. Though deemed self-defense, the incident was a sobering reminder of my volatile circumstances.

Depression and emotional instability plagued me during this time. However, even in darkness, there were glimmers of hope. The enduring friendships I maintained, such as with Leonard Todd, Phil Culmer and James Webb, provided anchors, helping me navigate the storm.

The Wilderness Years: 2001 to 2010

This decade saw me grappling with identity and purpose. While challenges persisted, I channeled my energies into writing, publishing a beginner’s guide to photography. The creative outlet offered solace and a sense of achievement amid the chaos.

Professionally, I broadened my expertise, mastering high-pressure water jetting—a skill that followed my earlier prison sentence—and expanding my qualifications as an industrial abseiler. These achievements reflected a relentless drive to evolve, even in the face of adversity.

Phil Culmer, who had become one of my closest confidants, played an instrumental role during these years. His sharp intellect and unwavering support were crucial, especially in navigating legal challenges and refining business strategies. Together, we weathered storms and celebrated victories, strengthening a bond that remains unshakable.

Finding Myself: 2010 to 2012

Emerging from the wilderness, I sought to redefine my narrative. Writing became a therapeutic process, culminating in my published book on photography. The act of creation was a declaration of resilience—proof that, even in adversity, I could produce something meaningful.

Friendships deepened during this time, with James Webb’s unwavering support guiding me through ongoing mental health struggles. My connection to the people who stood by me became a cornerstone of my renewed identity. Phil Culmer’s mentorship continued to shape my path, solidifying his role as both a friend and a vital collaborator.

The Best of a Bad Job - Reaching the Consciences 2013

Life took on a different hue as I began focusing on making the best of challenging circumstances. My experiences shaped a unique perspective, driving me to connect with others on a profound level. The relationships I formed—with extraordinary women like Sue, Cathy, June, and Sheryl—were both enriching and reflective of my complexity.

The Phantom of the Opera

The title is a metaphor for the masks I’ve worn and the stages I’ve graced throughout life. From the disciplined boy in Rayleigh and Leigh-on-Sea to the man overcoming struggles through resilience and reinvention, my story is one of contrasts—a symphony of triumphs and tribulations.

Phil Culmer, ever the strategist, has been a cornerstone in my journey, balancing my fiery nature with his calculated wisdom. Alongside lifelong friends like Leonard Todd and James Webb, he forms the fabric of a support system that has carried me through my darkest hours and brightest days.

Today, as I reflect on a life filled with lessons, my heritage and experiences converge into a narrative of hope and determination. The stage remains, and the performance continues.

SO LET'S DIVE IN!

A Prelude in Essex: The Seeds of Rebellion

It all began in the autumn of 1966—a time of subtle promise and unspoken destiny. Conceived in October 1966 on Hatfield Road in Rayleigh, Essex, my entry into the world was marked by an extraordinary twist. During my birth, I managed to tangle the umbilical cord around my neck into a true knot, forcing the doctors to use forceps. Mum has always maintained that this precarious start left its mark on my mental health. I was born on 28th July 67’—a day that, in retrospect, seemed destined to set me apart from the others.

Our family home was a private bungalow, unassumingly elegant and brimming with a comfort that many could only dream of. My father, a research engineer at Ford's Dunton, filled our lives with a spark of innovation and ambition, while my mother, the consummate housewife, nurtured our sanctuary with both iron will and tender grace. Life in those early days was the very picture of comfort—a calm before the storm of destiny.

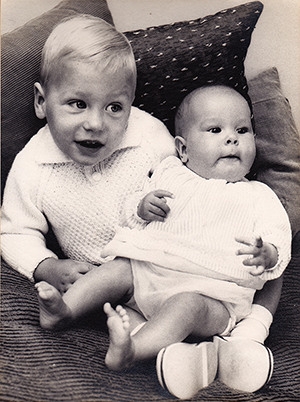

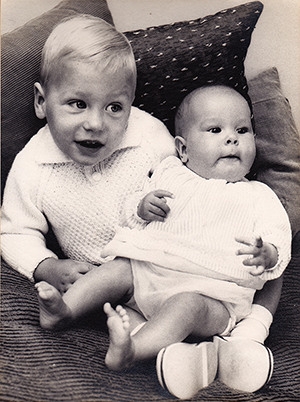

As fate would have it, the family’s tapestry grew richer still: in February 1969, my sister arrived at Hatfield Road, her presence heralding new bonds and rivalries that would colour our days with mischief.

Then, as if by design, our lives took a sudden turn. In 1971, we moved to Leigh-on-Sea—a coastal town that would soon become the stage for my youthful escapades. I began my early education at St. James's Church Hall on Elmsleigh Drive, a modest play school tucked at the west end of Manchester Drive. With a quick turn and up the hill, I found myself stepping into a world that would later fuel my wild imagination. Every day, my sister and I would take a secret shortcut through Blenheim Crescent—a passage leading to the warm, familiar embrace of my Nan and Granddad’s home, where mischievousness first whispered its tantalizing promises.

Even now, that memory shimmers like a scene from an extravagant film—a time when comfort and the thrill of the unknown intermingled in a dance that would shape the rest of my life.

1969

Roots of Rebellion Part 1 MANCHESTER DRIVE

Leigh-on-Sea in the early ‘70s was the kind of place where childhood could drift by in a haze of scraped knees, fish and chips, and the distant sound of the sea rolling in. It should have been idyllic, but my world was anything but. I was a wild card—an unpredictable force of nature—bouncing between adventure and trouble with reckless energy.

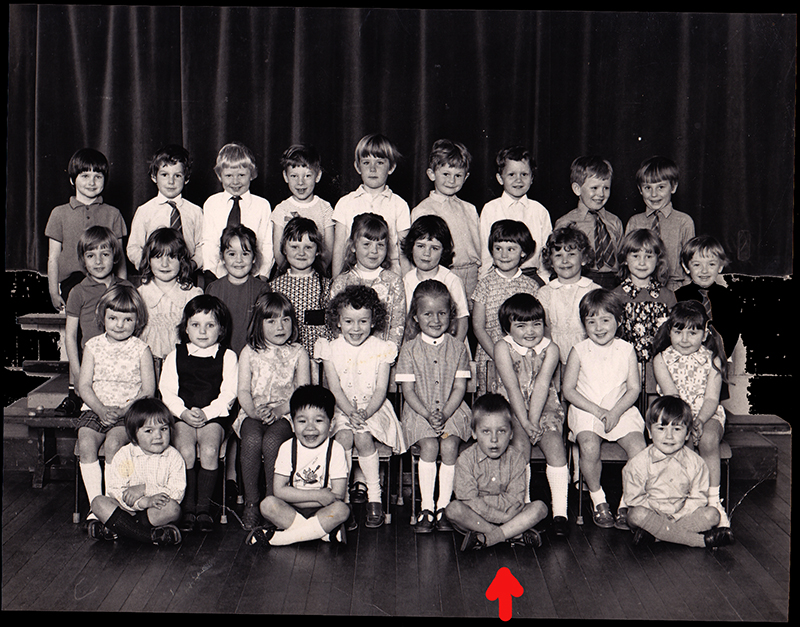

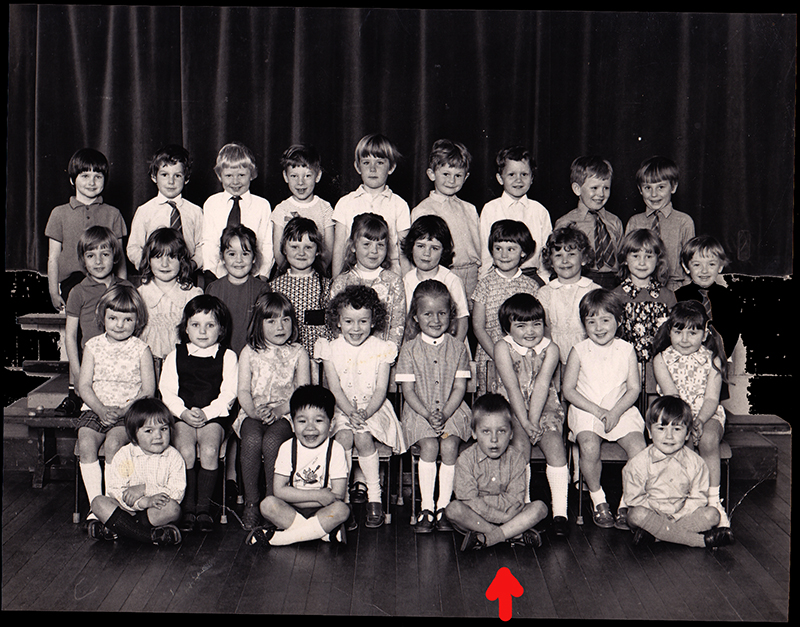

I started at Pall Mall Primary School around 1973. The details of those years are hazy—a blur of playground scuffles and classroom drudgery—but certain moments remain etched in my mind like deep grooves on a vinyl record.

Simon White was one of the few kids I truly connected with. He lived just up the street, barely a few hundred yards away, and we spent weekends wrapped in childhood escapades, most often camping out at the bottom of my family’s 135-foot garden. It felt like an adventure—as if we’d pitched our tent in some distant wilderness rather than in a suburban backyard. We’d whisper under the canvas, playing at being explorers, with only the rustling trees and the distant hum of cars for company.

Dad had gotten hold of an old military Morse code system, and Simon—far cleverer than I was—decoded the messages with the ease of a seasoned radio operator. My father, a man with an engineer’s mind, would sit tapping out messages while I listened, enthralled by the thrill of the dots and dashes, even though I barely understood them.

Then, suddenly, Simon was gone. He developed alopecia, and just like that, he withdrew from everything—from school, from our campouts, from life itself. He found new friends, people he was more comfortable with, and vanished from my world. It was my first real experience of losing someone—not to death, but to something just as irreversible.

School, for me, was a battleground. I wasn’t bullied—at least, not yet—but I refused to conform. Authority never sat well with me, and Mr. Eastwood, the squat, red-faced headmaster, seemed to take my very existence as a personal affront. Always beetroot red and on edge, he was like a kettle ready to boil over—and I was the match that sparked his fury.

But the real menace was Mr Rombow, the head teacher. A tall man always dressed in a crisp grey three-piece suit, with slicked-back black hair and a toothbrush moustache that made him look like a caricature of Hitler, he was cold, calculated, and had me on his personal list of targets.

Punishment was ritual. Mr Eastwood wielded the slipper liberally, and the cane was reserved for “special” occasions—of which I earned two, each time swearing I wouldn’t cry, each time failing. The worst part wasn’t the pain—it was the humiliation: the smirks from classmates, the whispered comments in the hallways. I was always at the bottom of the class, both academically and socially.

At home, I was a force of chaos. One moment, I’d be tearing through the house like a hurricane; the next, I’d be sulking in my bedroom for days, drowning in moods I didn’t understand. My mother—a woman of discipline and fire—had no choice but to match my wild energy with her own. (She beat me regularly—not out of cruelty, but out of desperation, trying to control something that simply refused to be controlled.) But punishment never worked. If anything, it just made me more defiant. Break something, get a beating, and then be taken shopping as an apology—that was the cycle. My mother, strict as she was, always tried to mend things afterward, her own way of saying sorry, and I learned that chaos had its rewards—even if it wasn’t helpful.

Then came my first true crime. Kimberley, my sister, existed in my world but was never truly with me. Sometimes we played together, but more often we were just two people sharing the same house. She became my unwilling accomplice in one of my first acts of real defiance: stealing from Mum’s purse. It was usually just pennies—small amounts enough to buy sweets at the shop by The Elms traffic lights on the way to school. Sometimes I’d share with Kimberley—not out of generosity, but because I figured if she was involved, she wouldn’t tell. She never seemed comfortable with it, yet she never refused. But I was the ringleader in that crime, and I knew it.

But those petty thefts were nothing compared to what came next. One afternoon, on my way home from school, I passed a church with a long row of schoolroom windows—three stacked one atop the other, running the full length of the building. Something about them dared me. The pristine glass, the way the sunlight hit it—it was too perfect. I picked up a stone and threw it. The sound of shattering glass sent a thrill through me. So I threw another. And then another. I didn’t stop until every single window was smashed.

That was the moment everything changed. At first, I felt no guilt—only exhilaration. But then I saw the faces of the onlookers, their expressions shifting from shock to anger. I’d gone too far. At home, Mum sat me down and, for the first time, looked truly lost. She didn’t shout. She didn’t beat me. She called Social Services. It was official: I wasn’t just a handful—I was a problem. And I didn’t know then that that act of destruction—the sheer thrill of breaking something—would echo in ways I couldn’t yet imagine.

For the most part, my dad worked at Ford Dunton Research Centre in Essex, but on weekends he always had a friend’s or customer’s car parked out front, and I remember him building—or helping me build—one or two fantastic go-karts. By then, I was also involved with a new friend from the other end of Manchester Drive, Mark McMarne. Manchester Drive was a street of two ends—the private end where I lived and the council end where Mark lived—but that never came between us. Besides, he nearly always had new togs. I suppose I did too—usually following a beating from Mum.

Alongside their motorcycle work, my parents also ran a cycle factory called Magnum Cycles. One day, Dad came home with a brand-new silver racing cycle for me. I was around ten, still living at Manchester Drive, and the bike was slightly too big for me, but it was meant for me to grow into. I rode that cycle for years, though like most of my possessions, it eventually got battered from being dropped and left out in all weather. Looking after things wasn’t exactly my strong suit back then—I had no real values at that stage of my life.

Dad always had a company car, which changed almost annually—from a blue Ford Prefect to a bronze Ford Zephyr and finally a Ford Cortina Ghia Mk4. But later, he left Ford and embarked on an engineering venture with a crook called Malcolm Mascerinas, who, in the end, robbed my dad of approximately £40,000—big dough in ’78. They had converted warehouses into development workshops out by Surrey Wharf on the Thames. But that was not before the entire family moved to Hayes, on the outskirts of the London borough of Bromley, to fit in better with this new venture.

1974

1976

Roots of Rebellion – Part 2 KETCHILL GDNS

We now had a large four-bedroom house, where the huge hallway was wood-panelled, and there was a nice garage attached to the side with a short driveway and a smallish front garden. But it was a much smaller rear garden, although that didn’t stop me and a new friend, Brian Rowland, from camping out in it.

But this new environment came with many difficulties, from not getting on at school to setting light to a gas canister in the new garage. Thankfully, my dad saved the day. Mum screamed, and he charged in, ripping off his Ford sports jacket and smothering the flames with it before manoeuvring the bottle into the garden and pushing it away with his foot so it rolled safely into the open. A hero. I didn’t realize the gravity of what I had done until years later.

Just before we moved to Hayes, I was set to change schools soon and would have been going to Belfairs Secondary School in Leigh-on-Sea. Instead, I went straight into my new school, Hayes Secondary School, which was a considerable upgrade—full-blown science labs, better facilities. But despite my parents’ efforts, I struggled terribly.

I made a couple of friends near home, and we soon found a shared passion—skateboarding. I had some fantastic boards. My dad even built me a board almost five feet in length, called a speed board. It had new wide trucks, red wheels, complete with new bearings and steering bushes. We had a steep tarmacked road right opposite our house on Ketchill Gardens. Wow, did I do some fast skateboarding—until the day I crashed badly at the bottom and broke my left lower arm. But even this didn’t stop me.

Dad was always a keen weekend freshwater fisherman and, from time to time, he took me along. Those were the moments I looked forward to most—not for the fishing itself, but for the ritual that came before it. The best part was the night before—digging for worms together in the garden, a father-and-son tradition. We’d pour warm soapy water around the damp soil, watching as the earth wriggled to life, thick-bodied worms rising up in search of air. Then, with the precision of hunters, we’d dig—just turning over the topsoil, careful not to damage our prize, collecting the fattest, juiciest ones for bait the next day.

I was always excited doing things with Dad, even if the enthusiasm never quite carried over into the actual fishing.

Once we reached the riverbank, something changed. My father’s world and mine split into separate spheres. He would wander off, setting up his spot, finding his rhythm, while I sat further down, staring at the water, rod in hand, unsure of what to do next. I don’t recall him ever teaching me how to fish—how to properly cast a line, how to wait, how to read the water. It was as if we’d shared the build-up, but when the moment arrived, I was left to figure it out alone.

And so, I rarely caught anything.

I’d watch Dad from a distance, completely absorbed in his own world, while I grew restless. After an hour or two, the thrill had evaporated, and I’d start thinking about home, the excitement of the night before replaced by boredom. Eventually, I’d wander back over to him, hoping to signal that I was done. He didn’t say much, just nodded, packed up his gear, and we’d leave.

Looking back, I think he preferred going on his own. Perhaps Mum pressed him to take me, imagining it would be quality time, but fishing was his escape, his solitude—and I was just tagging along.

Still, even though I never truly learned the craft back then, something about those trips stayed with me. The peace of the water, the quiet patience it required, the way time slowed down—fishing would be in my blood from here on, right up to the present day.

During our eighteen months or so at Ketchill Gardens, my parents bought a large four-berth caravan—a move that would mark some of the best times in my childhood.

I loved caravanning. I loved camping.

There was something about being away from home, being out on the road, waking up in different places that thrilled me. The freedom of it, the adventure of it, even if it was just parked in a quiet field somewhere—it felt like an escape.

We took one or two great holidays in that caravan, traveling to different parts of the country. Those were the times when our family felt most at peace, as if the tension of everyday life back home had been packed away and left behind.

But those moments were fleeting.

Because life at home was about to change forever.

After the breakup of my father’s partnership at Malam Industrial Research, things took a sharp turn.

Dad had been burned badly. Malcolm Mascerinas had walked away with forty grand, and my father was left with nothing but the bitter taste of betrayal.

But my parents weren’t the type to lick their wounds and give up.

Instead, they did something bold—something that would define the next era of our lives.

They decided to break out on their own.

No more dodgy business partners, no more failed ventures. This time, they were taking full control.

Within weeks, the tension in our home was palpable. Dad’s determination was fierce, and every late-night phone call and hushed discussion at the kitchen table only added to the charged atmosphere. Even as the adults around me were caught up in their high-stakes gamble, I kept my focus on my own kind of chaos. I wasn’t about to slow down or change course—my reckless streak was as alive as ever.

There were moments when I caught a glimpse of the seriousness of their struggle. An afternoon spent watching Dad restore an old engine in the garage, the clatter of his tools echoing against Mum’s anxious reassurances, reminded me that life had suddenly become a high-stakes game for the grown-ups. But while they calculated risks and measured every loss, I was still chasing the next thrill, untouched by any newfound caution.

The air was thick with anticipation and risk. I felt the rush of adrenaline with every rebellious act, my daring exploits a stark contrast to the cautious manoeuvres of my parents. The world around us was shifting, yet my own orbit remained unaltered—full of wild, untamed energy, with no room for responsibility or restraint.

And so, as our family embarked on this bold new gamble, I continued on my own path—undaunted, reckless, and eager for the next burst of chaos. While the adults plotted a future that might rescue us from the fallout, I stayed firmly in the moment, my rebellion burning brighter than ever, oblivious to the weight of what lay ahead.

Roots of Rebellion – Part 3

After months of scouring the country for the right business opportunity, my parents finally struck gold. They bought a petrol station complete with workshops, a shop, a paint area, a showroom, ample parking—and even a Bedford Truck converted into a full-blown recovery vehicle. This site, on the edge of the village of Sibsey along the A16 (the main road from Boston to Spilsby), became our new home. Adjacent to the business was an average three-bedroom country cottage with a nice garden and stone driveway, a large pond, and low ceilings laced with timber beams. At least my sister and I had our own bedrooms there. We moved in June ’79.

In July, on my 13th birthday, Mum gifted me a record player—a Dansette-style set with a lift-up lid and two controls for volume and tone—and my first album, Elvis Presley’s Separate Ways. Not long after, Dad brought along one of his former employees, Phil Stevens—a quiet, pockmarked fellow with a slightly pointy nose—who introduced me to another album by ELO called Discovery. That was my musical awakening. Soon after, an album by The Who followed, and through a friend’s suggestion, I bought an external amplifier and some speakers. I even remember Dad coming into my room with a soldering iron and a few tools to wire my record player, amp, and speakers together. Just like that, I became a “sound man” with the beginnings of a great record collection. Meanwhile, my sister would record Top of the Pops on a tape recorder in her room—dressing up and playing with our Boxers, Bruce and Major, even though the dogs never really appreciated the get-ups.

Not everything in my new life was as wonderful as music. I soon started at William Lovell Secondary School—a far cry from the comforts of our cottage—located miles from home in another village. The headmaster, Jack Dyde, was a massive man in his early 60s with little patience. He made it his business to target me: slippering me frequently and even dragging me by one leg through the school, swinging me into walls and coat pegs. One bitter winter day, after I’d thrown a snowball (against explicit orders), the ball hit the glass by a door just as he was coming through it. Snow covered him as he thundered toward me. In a blur, his fist connected with my nose—breaking it—and then he dragged me across the yard, through the door, along the hallway, and into his office. Mum was called, and though she wasn’t entirely happy about the broken nose which she only discovered on my return home and the humiliation, that was the end of it. I left school just months later.

Most teachers despised me outright—except for two. Mr Sykes, my technical drawing teacher, and Mr Alan Brader, one of my sports teachers, saw something in me. I recall one scorching summer sports day: I was loitering around the bike sheds, smoking and disinterested in sport as usual, when a classmate hollered that Brader was looking for me. Before I knew it, I was togged up on the starting line for the 1500m run. The race was gruelling—I lagged behind from the start until, with 300 meters to go, something inside me snapped. I kicked off my shoes and surged forward with a burst of raw energy. As I came around the 200m mark, I caught up with the back runners; and as I rounded the final 100m—with Smith, Henderson, and the finish line ahead—I powered on, passing Smith and Henderson, and took the finish. Smith and Henderson were the school’s fastest runners. That evening, Brader went straight to my parents, pleading with them to get me more involved. It was too late—I was already lost. (If only Miss Vipond, my first crush and another sports teacher, had been there; I might have listened to her.)

By the time I was 15, things at school had taken a darker turn. My pronounced Roman nose and raw southern accent made me an easy target, and bullying became a constant companion. Every journey on the dedicated school bus filled me with dread as I anticipated fresh torment. On one sweltering summer day—the day I even started thinking about joining the army to defend the Falklands, though I was still a perpetual victim—the bus pulled into a layby known as the Tree House. This spot, marked by a tall tree and a wooden triangle shelter built around the tree with a pitched roof, was where all the kids gathered. I tried, as usual, to slip away unnoticed. But my nose, like a beacon, betrayed me. “Hilly! Oi, Hilly!” the jeers rang out. I raised my hands, pleading for mercy as shoves and taunts escalated.

Thinking the fight was over, I turned away. But within two steps, Bourne, the schools champion boxer called, “Hey, Hilly!” I turned—and was struck hard on the left side of my face with a broken brick. I fell hard, yet like a spring-loaded mechanism, I bounced back. In a burst of uncontrolled fury, I lashed out with my right fist, dropping my attacker like a sack of shit. I didn’t stop there—I leapt onto him, pinned him down astride his chest, grabbed his hair, and pounded his face repeatedly. I was never gonna stop until it was over, over, over. It was only when I felt two strong arms yank me away that I realized Grenville Page had intervened. Without a doubt, Grenville saved Alan Bourne’s life that day by stopping me before I could do any more irreversible damage. Grenville would later become a close friend—and the one who introduced me to the scooter scene, as he was busy building a Lambretta “cut-down” right in our workshops.

As my 16th birthday approached, the dream of breaking free on two wheels loomed large—in a different form now. But my parents were adamantly against the idea; they insisted that two wheels were a death trap on modern roads. With some pocket money saved, I found a metallic blue Honda SS50—a wreck, but mine nonetheless. I badgered Dad to fix it up, despite Mum’s constant “no.” After much pestering, Dad finally agreed. He took the bike to another workshop he ran with a couple of chaps, while my anticipation grew. I already had my provisional driving licence—I just needed a ride. On the eve of my birthday, Dad promised, “Don’t worry, we’ll go over together in the morning and get you on the road.” I tossed and turned with excitement all that night.

The next morning, Mum was unusually involved. We drove to the shop and workshops where the SS50 was to be fixed up. But when Dad opened the door, I found not my Honda, but a brand-new Yamaha RD50LC in jet black. I couldn’t believe it. Mum had decided that if I was to ride, I’d have a better chance of surviving on a new machine rather than an old banger. Her condition was strict—I was to ride around the countryside following them until I was visibly comfortable on it. And once I was, that summer I discovered a newfound freedom: riding round the local lanes, feeling the wind, and exploring every back road and hidden corner of the countryside.

In the March of ’84, that rebellious freedom took another twist. I attended my first scooter rally in Skegness and met up with Grennie—someone I’d come to know well through our shared passion for all things motorized. Funny enough, I should mention Skegness, because at a different time, just before this I had gone there with a friend and ended up getting my first tattoo on my left forearm. I was so pleased to have outsmarted Mum that day. “There’s nothing you can do about that now,” she said—I smirked, though I later realized how foolish it was. That stunt was just the beginning; over the years, I’d amass about 15 tattoos covering both arms, almost like sleeves, each one a marker of the rebellious path I’d chosen.

That summer, while riding near a static caravan site, I parked on a bridge for a smoke. There, I met Donna O’Grady—a 25-year-old from Sheffield who was visiting with her family for a couple of weeks. We hit it off immediately: we kissed on the bridge within a few days, exchanged numbers, and before long, I was utterly infatuated. I was only 16, but I thought I was in love.

At the same time, I was working on a Youth Training Scheme—day-release college studying engineering while servicing, cleaning, and selling cars at Dad’s business. I was on a measly £25 per week, and frankly, they were just using me. Soon enough, Donna and I hatched a plan for me to leave home. I was to take my Yamaha on the train and meet her at the station—she even promised to sort out a place to sleep with her grandmother. It didn’t work out as planned. My first night ended with me lying along the seat and tank of my Yamaha in a local park as it snowed. Before I knew it, I was caught in what you’d now call a toxic relationship—homeless, jobless, with no plan or money. Despite it all, I oddly enjoyed the freedom, though those months were some of the worst of my life. I spent Christmas wandering the streets in search of food. Then, in the New Year, I’d had enough and decided to go home. By then, my Yamaha was a wreck, and I abandoned it.

Back at home, I couldn’t bear leaving Donna behind. In desperation, I started scheming ways to win her back. After seeing an ad in the paper, I somehow secured a rental flat in Skegness—an outcome I still can’t quite explain. That said, I had become more street wise through my time away from home. Donna joined me, and my parents even drove us over to set up our new home together. But a few weeks later, Donna left me for another tenant in the same block. Heartbroken, I called Mum. That night, they drove over and collected me, taking me back to the family home. I didn’t know then that within three days of returning, I would have a complete breakdown—and soon after, Donna and her new man had vanished to Sheffield.

In a final act of desperate rage, I concocted a plan to hunt them down. I remembered that Dad always brought home the day’s takings in a bank bag, along with cheques and paying-in books. One night, after everyone was asleep, I crept downstairs, grabbed the bank bag along with Dad’s car and business keys, and set my plan in motion. I drove Dad’s car to the garage where he, along with brothers Jed and Jim, ran another business. I unlocked the office, stocked up on stolen cigarettes and some munchies, and then spied a pale blue Mk1 Ford Escort Mexico in the lot. It was beautiful—and that was what I was taking. I found its keys in the cabinet, filled it up at the petrol pumps, and parked Dad’s car in its space. I even put a “For Sale” sign in the window, hoping to buy myself some breathing room.

I had a rough idea of my route as I made my way north through village after village. The Mexico proved powerful and fast, and though I spotted police lights several times, I thought I had eluded them—until I found myself on a dual carriageway heading straight into central Mansfield. Suddenly, the police lights appeared in my rear-view mirror, and a roadblock materialized ahead. With no escape, my 83-mile run ended in Mansfield cells. Dad eventually came to collect the Mexico, but he didn’t visit me—he simply went home. That, more than anything, shook me. Sometime in the middle of the night, I was escorted in handcuffs to Boston Main Police Station.

To be continued

My Cars and the Road to Chaos

The Morris Marina 1.8TC wasn’t just a car; it was a symbol. My first official vehicle, it marked a rite of passage—a statement of freedom and independence. I’d grown up surrounded by cars, working on them with my dad in the family garage, turning rusted relics into quick sales. But this one was mine, a step into adulthood. I passed my driving test on August 4, 1984, seven days after my 17th birthday, and by the next day, I was ready to leave the family home and rejoin my mother in Leigh-on-Sea some 200 miles away.

My father had other ideas. “Take the 1.3L,” he said, handing me the keys to the Marina’s lesser sibling. It was a clear downgrade—no power, no radio, and barely enough engine to pull out of the driveway. But I didn’t argue. My dad, ever practical, was hedging his bets. If I smashed it up, better to lose the banger than the 1800 TC. I scrounged an old stereo from the garage, wired it up, and loaded the car with tapes and belongings. With a mix of nerves and excitement, I hit the road.

The drive south was unforgettable—my first taste of real independence. I still remember the glow of the streetlights on Progress Road as I navigated Leigh-on-Sea late that night. Purple Rain by Prince and Drive by The Cars echoed from my makeshift stereo, the soundtrack to my first journey into the unknown. I felt alive. But reality has a way of humbling you fast. Two weeks later, racing a Ford Escort Mexico on the A127, I misjudged an amber light. He stopped; I didn’t. Both cars crumpled in the collision, and I was left standing in the wreckage of my first attempt at freedom.

For months after, I bounced between jobs, unable to settle. My original plan—joining the army—had fallen apart. I’d even been accepted into the Parachute Regiment, but something inside me balked. It wasn’t fear of danger—it was the fear of regimental discipline, the rigid structure that would chain my rebellious spirit. The army might have offered stability, but the fear of losing my individuality loomed too large. I needed something else—a path that felt uniquely mine.

A “sky’s the limit” ad in the paper caught my attention. Loft insulation sales didn’t sound glamorous, but the promise of big earnings hooked me. My mother, seeing my determination, took me shopping for new clothes. She wanted me to look like someone destined for success, and for the first time in weeks, I felt like I could be.

The interview was brief but revealing. Peter Restorick, the manager, sat behind a desk with a clipboard in hand. His blond-highlighted hair and Mexican-style mustache gave him an almost theatrical presence. “Go knock on doors and ask about loft insulation,” he said, handing me a pad and pen. I didn’t hesitate. I turned and walked out, ready to start knocking. That boldness earned me the job and left an impression—Restorick would become a figure I’d remember for years to come.

For the first few days, I shadowed Len Whally, a seasoned veteran of door-to-door sales. Len was tall, no-nonsense, and relentless in his pursuit of results. By Thursday, I was on my own, knocking on doors and delivering my pitch. My first sale was a rush—proof that I could do this. By Friday, I’d closed three more deals and pocketed £100 in 2 days. I was hooked.

In the months that followed, I flourished. Len Todd and Kevin O’Shea, seasoned professionals in the trade, became my mentors. Len was a commanding presence—tall and of solid build, with firm, jutting features that seemed carved from granite. His handshake matched his appearance: strong, deliberate, and full of confidence. He was the archetypal businessman—focused, efficient, and methodical. Kevin, on the other hand, was nearer my stamp—closer in build and attitude. He was brash and charismatic, a natural salesman who could charm anyone with his wide grin and easygoing nature. Between the two of them, I learned the art of persuasion and the science of closing deals. Around this time, Wham—the pop duo of George Michael and Andrew Ridgeley—became the soundtrack of my life, their upbeat energy perfectly matching my rapid ascent.

Len also had his own way of rewarding hard work. On Fridays, after a particularly good week of sales, he’d hand me a small bag of weed—a token of appreciation and camaraderie. I didn’t use it myself, but I passed it on to friends who appreciated it more than I at this time. It was just another way Len showed his unconventional but effective leadership style.

Soon, I was the one others wanted to shadow. With every door I knocked on, my confidence grew, and so did my results. My sales skyrocketed, turning each interaction into a stepping stone. At the peak of my performance, I achieved an astonishing sales ratio of 1:1—every door knocked became a sale, a feat that cemented my reputation within the team. The commissions flowed in, piling up faster than I’d ever imagined. My earnings transformed my bedroom into a personal vault, with cash stuffed under the mattress, piled in jars, and scattered across the floor. At just 18, I was living a life many would envy.

Success brought rewards. As team leader, I earned override commissions on my team’s sales and was given a maroon Ford Escort Mk 3 company car. Within months, I upgraded to a white XR3i Cabriolet, a sleek machine that matched my growing confidence. Life at 18 felt untouchable.

But success has a way of amplifying flaws. My aggressive tactics, once an asset, began to backfire. Cancellations piled up, and my sales figures faltered. Then came the final blow: the company folded. Colin Bland, the enigmatic figure at the helm, was a large, rotund man with a completely bald head, whose sheer size made him a memorable presence. He disappeared overnight, leaving chaos in his wake. About ten days later, Len Todd tracked him down. I’ll never forget the look on Len’s face when he turned up at my place, a fistful of cash in hand. “This is all we’re getting,” he said, his voice tinged with both anger and resignation. It wasn’t much, but it was something—a small glimmer of closure in an otherwise devastating loss. That moment solidified what I already knew about Len: he wasn’t just a colleague or a mentor; he was someone who could be trusted even when the odds were stacked against us.

Returning home was a bitter pill. The family bungalow in Leigh-on-Sea was overcrowded and suffocating. I was relegated to a makeshift loft room, accessible only by a ladder. My mother demanded £50 a week for rent and food—a steep price for someone with no income. I frittered away my savings, and I now owed her £1,000, a debt that loomed over every interaction.

The pressure was relentless. My mother’s criticism was sharp, her disappointment palpable. It pushed me to desperation. Martin, a childhood friend, became my accomplice and getaway driver in a reckless scheme to escape. With his dad’s handgun, we planned to rob a security van during its cash drop. It wasn’t well thought out, but it felt like my only option.

The heist was a disaster from the start. Arriving late, we missed the perfect window, but desperation drove me forward. After the heist, instead of laying low, Martin and I made a fatal error—we drove around the area, curious to see the commotion we'd caused. It was a foolish move that would seal our fate. As we fled the scene in Martin’s battered Mk2 Ford Cortina, the weight of what we’d done began to sink in. The adrenaline coursing through my veins turned to dread as our escape route took us along Fairfax Drive. As we entered the Albany roundabout, police vehicles swarmed us from all directions with chilling precision, their vehicles boxing us in like predators closing on prey. The sound of screeching tires and shouting officers filled the air as our car came to a jarring halt. Before I could make sense of it, weapons were trained on us, the barrels gleaming under the harsh glare of their headlights. We were pulled from the car, the gun still hidden under the seat—a damning piece of evidence that sealed our fate.

The trial was brutal. Martin turned Queen’s evidence, blaming everything on me to save himself. His betrayal stung more than the sentence. He received 18 months, while I was handed six years. It was a harsh lesson in trust and consequences.

Looking back, the robbery wasn’t about money. It was a desperate bid for freedom—a way to escape the suffocating pressures of home and my mounting failures. It cost me dearly, but it also set the stage for a deeper understanding of myself.

TO BE CONTINUED..